by Paul Knepper

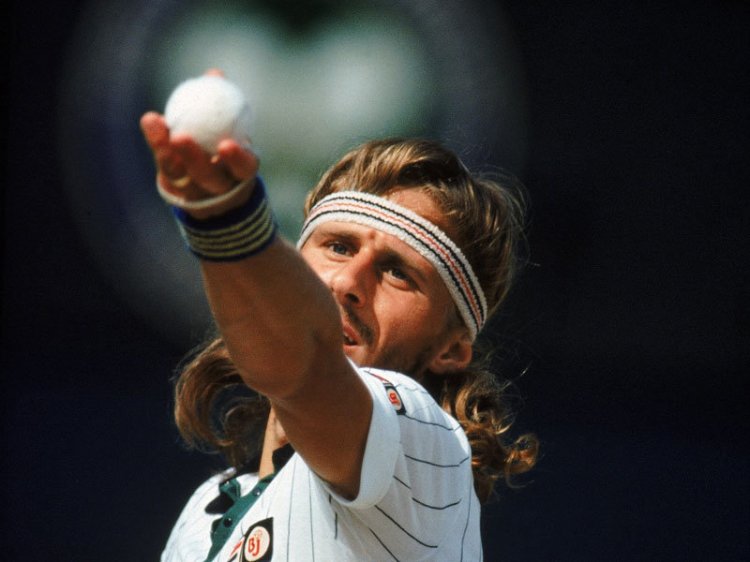

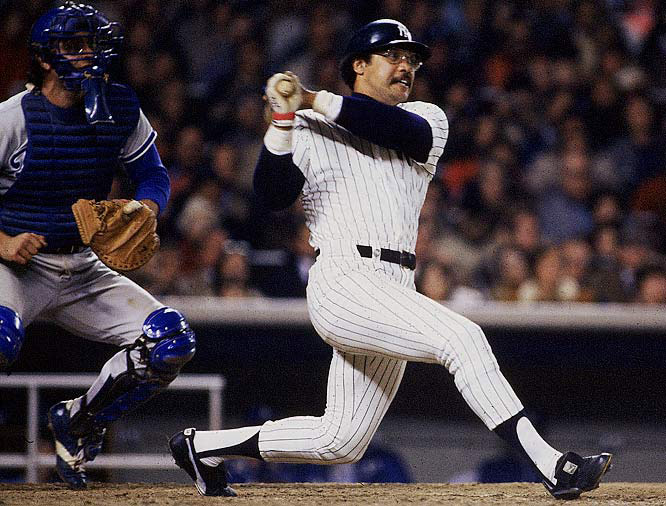

Tennis can be a lonely sport. You’re all alone on the court. There’s nobody there to share the joy of victory or burden of defeat. There’s no one to lean on when you’re tired or to commiserate with on the road. That was especially true for Jimmy Connors who made a point of distancing himself from the other members of the tour.

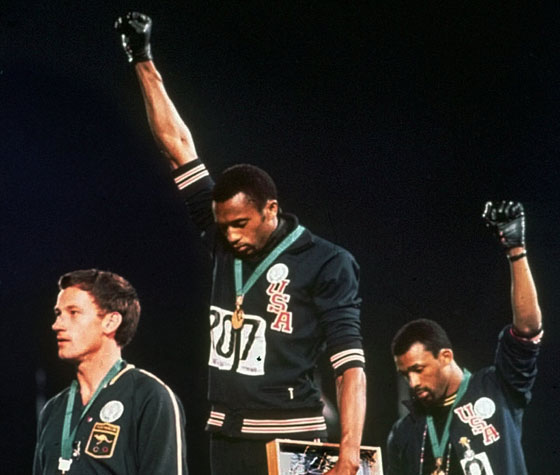

Such isolation lends itself to the possibility of an emotional connection between athletes and fans which doesn’t exist in team sports. Occasionally an individual athlete develops such synergy with the crowd that they feed off each other’s energy and elevate one another to greater heights. Muhammad Ali did it with the people of Zaire when he fought George Foreman in 1974 and Jimmy Connors achieved it with the New York crowd at the 1991 U.S. Open.

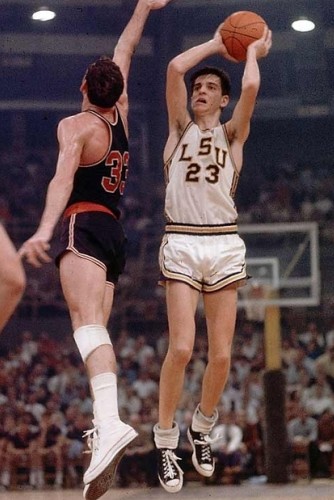

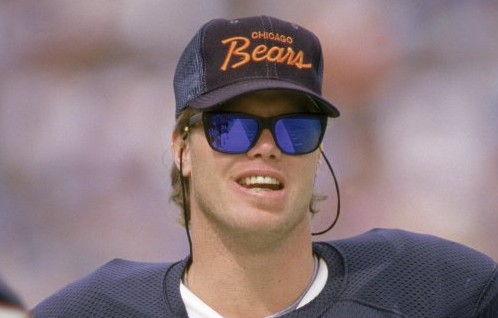

Connors was born and raised in East St. Louis, Illinois, but for all intents and purposes he became a New Yorker. He played his best tennis at the U.S. Open in Flushing Meadows, Queens, where he won five of his eight grand slam titles, and was the only player to win the tournament on three different surfaces (The Open was played on grass until 1975, then switched to clay for three years, before changing to hard court in 1978.)

New Yorkers embraced him as one of their own. They saw a bit of themselves in the feisty left-hander with the indomitable will. Connors didn’t try and out finesse his opponents with tons of topspin or a delicate touch; he came right at them with his flat ground strokes and kept them on the defensive by taking the ball on the rise.

Fans appreciated that Jimbo wore his emotions on his sleeve and responded in kind, boisterously exhorting their hero on. Connors returned the favor with a smile and a wave or by cracking jokes for the cameras. He fed off the energy in the stands, which ramped the New York crowd up even more.

Jimmy had been ranked #1 in the world several times, once for 160 consecutive weeks, and won a record 109 tournaments, but after battling injuries in 1990 and 1991 he was ranked 174th and had to win a qualifying match just to gain entrance to the ’91 U.S. Open. The tournament began a week shy of his 39th birthday; in a sport in which 30 is ancient, nobody expected him to advance very far. But Jimbo never gave a damn what other people thought. He’d made a career out of defying the odds.

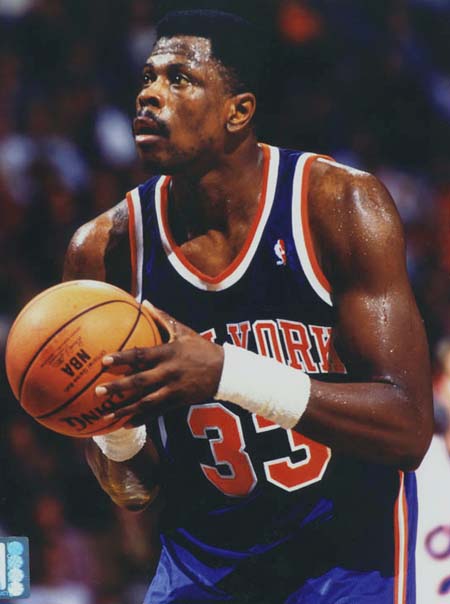

In the first round Connors faced Patrick McEnroe, younger brother of his longtime nemesis John. Patrick was no slouch himself, ranked 35th in the world and playing the best tennis of his career. Behind a strong serve and volley game, he captured the first two sets and took a 3-0 lead in the third.

The old man was short of breath and the crowd at Louis Armstrong Stadium had started shuffling out. John McEnroe admitted the next day that he changed the channel, believing the match was over. Up Love-40 in the fourth game, Patrick was about to put the nail in Jimmy’s coffin.

Suddenly, Connors discovered the fountain of youth. He zeroed in on Patrick’s serve, began stringing together points and came back to win the third set. Spurred on by the rapture of the fans that had remained, he finished McEnroe off 6-2, 6-4. The match lasted four hours and 18 minutes and ended at 1:35am.

Jimbo won his next two matches in straight sets, knocking off Michiel Schapers and the # 10 seed Karel Novacek. The energy of the crowd multiplied with each win and nobody on the tour knew how to create and harness that energy like Connors. It seemed to sustain him as he advanced through the tournament, compensating for the lack of juice in his legs.

As Jimbo took the court on his 39th birthday for his fourth-round contest against fellow American Aaron Krickstein, the fans at Louis Armstrong Stadium greeted him with a rendition of “Happy Birthday.” He needed them more than ever if he was going to beat the 24-year-old Krickstein.

Connors and Krickstein split the first two sets. Jimbo looked exhausted as he fell behind early in the third and made the risky decision to tank the set in order to preserve his energy for the fourth and fifth sets. The fourth went according to plan, but in the fifth set the younger Krickstein had Jimbo on the ropes at 5-2.

Once again, Connors came storming back. After big points he pumped his fist and the fans responded with a rousing ovation. At one point in the fifth set Jimmy looked into the camera and relayed the sentiment of the crowd, “This is what they paid for! This is what they want!” Krickstein was overwhelmed by the Connors mystique and the roars cascading down from the stands and Connors closed out the match in a fifth set tiebreaker.

After four hours and 42 minutes, the old warrior pointed to the crowd on all sides of the court to express his gratitude for their support. It was as if he was saying, “this is your victory too.” After the match, John McEnroe went to the locker room to congratulate his old rival. “I’ve got to go in there and touch him and see if he bleeds” Mac said.

Connors’ next opponent, in the quarterfinals, was Dutchman Paul Haarhuis, who had defeated #1 seed Boris Becker earlier in the tournament. Once again Jimmy fell behind, losing the first set, and trailed 5-4 in the second, with Haarhuis serving at 30-15, two points from winning the set.

It was unlikely that Connors’ could endure another five-set match so he had to make his move. He won the next two points, then delivered the most memorable sequence in U.S. Open history:

Haarhuis charged the net behind a strong backhand and all Connors could do was lob it back. Haarhuis slammed an overhead to Connors’ backhand side and Connors, back to the wall, lobbed it over again. Haarhuis smashed a second overhead and Connors was able to backhand it high into the air once more. This time, Haarhuis slammed the ball to Connors’ forehand side. Looking as spry as ever, the old man lunged to his left and lobbed it back.

By this point, Haarhuis was exhausted and his next overhead was his weakest. Connors pounced on the opportunity and drilled a crosscourt forehand. Haarhuis volleyed it back and Connors crushed a backhand down the line to win the point.

Connors unleashed a flurry of passionate fist pumps as the exalted crowd jumped to its feet and roared with appreciation. If the rally symbolized Jimbo’s indomitable will, then the ecstatic look on his face afterwards reflected his unparalleled love for the game.

The astonishing rally left Haarhuis emotionally drained. Connors won the third set in a tiebreaker and closed out the match 6-4, 6-2. Louis Armstrong Stadium erupted after the final point and once more Jimmy gave thanks to his fans.

The fountain of youth dried up in the semifinals, as Connors fell to Jim Courier in straight sets. Stefan Edberg won the tournament, but it was Connors who made it a U.S. Open to remember. For 11 days he enraptured every one who was there or tuned in to watch and those of us who did will never forget it.